So it’s been a few months and now we are back at HCA for another module, this time entered around the processes of editing and post-production. As our brief is to work around found footage, and to minimise creation of content in order to work on our editing skills, I have decided to resume working on a project which I have been thinking about since 2013. Having reedited my previous film, Black & White, with the help of my brother, it became obvious to me that the aspects of my movie which didn’t work were mostly due to poor editing, and to an inability to take a step back and go in a different direction with my editing once my initial ideas proved to not be working quite adequately. The exercise is therefore interesting to me as it brings focus towards editing ; not depending on footage that one creates means that if the film is a failure, then it is entirely down to editing… And that therefore it can easily be corrected.

I have been passionate about Hong Kong cinema for a few years. The hysteria of those films, their constant creativity, their complete lack of limits and their tendency towards astonishing visual bravado has seduced me as a viewer before I even reached my teenage years and has profoundly influenced my practice as an adult. In 2013, I started taking interest in the history of Hong Kong cinema as I felt that most of the films I saw had been directed between 1986 and 1997, before Hong Kong’s handover from Great Britain to China. In Asia, Hong Kong stands tall and alone as a cinematographical entity, for a simple reason : while it is located in chinese territory, it was under british crown rule from 1841 to 1997. As such, the hongkie cinematic approach is unique within chinese cinema : while taiwanese and continental chinese cinema have a staticity to them that is aimed to support the subject matter, HK films tend to disregard subject matter to focus on visual experimentation and entertainment. While this is a generality which does not necessarily apply to most of the local production, it was also what attracted to Hong Kong films in the first place, not knowing that there was a plethora of films directed before 1986, and that Hong Kong cinema before the 80’s was radically different from most of what we know here in Europe. In the United Kingdom and in France, for example, Hong Kong cinema is mostly known for Bruce Lee and John Woo’s works ; pieces like A Better Tomorrow (on which I have written an essay here) or The Killer. My favourite director in Hong Kong, however, has always been Tsui Hark. A mad genius whose visual bravado is as incredible as his ruthlessness as a producer, the man has single-handedly revolutionised Hong Kong cinema in depth and brought it into a new age ; but in 2013, I was mostly interested in the films he made before he encountered success, and most particularly in an officious trilogy which was released in France (and only in France) by HK Video : the trilogy of chaos, made up of three films, all equally innovative and different. The Butterfly Murders, the first film of this trilogy, was a wu xia pian ; a chinese chivalry film ; which took a peculiar stance on the usual codes of the genre as it scientifically explained its fantasy elements and prioritised its police investigation subplot over its combat scenes. Using the gimmick of murderous butterflies bred to kill, Tsui Hark, through sheer guile, made his wu xia film into a veritable eastern giallo, as his piece went from killing to killing through an atmosphere heavy with eerie lighting and leather-caped figures. But more importantly, it was when I saw that film for the first time that I was introduced to the notion and idea of Hong Kong New Wave.

Stills from The Butterfly Murders

The way I came across this knowledge was through an introduction to the film, available on my DVD, which explained quite briefly that The Butterfly Murders was more than the first film of his illustrious director, it was the first truly important film of this movement which local critics referred to as the Hong Kong New Wave. While the HKNW has no links whatsoever with the french Nouvelle vague, critics defined the HKNW using that term as they believed the directors who composed were similar in spirit to the directors of the french movement. They were all young people, who had studied abroad and worked in television, and who brought a different angle and a different perception to a movie industry which had revolved around major studios like the Shaw Brothers for more than thirty years and was running very much short of steam. Those directors ; Tsui Hark, Ann Hui, Ronny Yu, Alex Cheung, and Yim Ho, to name just a few of the most important ; said no to the studio system and shot their films on the streets, on the outskirts of Hong Kong, with low budgets and very little means but a virtual unlimited amount of furious creativity. A few years later, after having found and watched many of the Hong Kong New Wave most well-known flicks, I read Pak Tong-Cheuk’s Hong Kong New Wave Cinema : 1978 – 2000, which provides detailed insight on Hong Kong’s history of film, the emergence of the New Wave and their subsequent absorption into the mainstream hong kong film circuit. One of Pak Tong-Cheuk’s most significant contributions to the theoretical aspect of the movement is that he was, to my knowledge, the first to effectively date it : it starts in 1978 with Yim Ho’s The Extras and ends in 1984 with… A number of films. Some theorists claim the last film of the Hong Kong New Wave is Yim Ho’s Homecoming, others that the movement ended when the unofficial leader of the movement, Tsui Hark, created his own studio, Film Workshop, in which he could create the films he wanted the way he wanted to make them without the interference of major industrial companies like Shaw Brothers or Golden Harvest.

Stills from Homecoming. The film, while being considered both one of the best chinese motion pictures and one of his illustrious director’s best features, has still never been properly distributed and is therefore only available to viewing in a highly degraded VHS that most of us have ripped straight off YouTube.

However, my absolute and utter fascination for Hong Kong New Wave Cinema only came about after I started exploring the films of artists other than Tsui Hark. It was with Patrick Tam’s The Sword, a wu xia film which explores the myth of the wandering swordsman with a crepuscular approach that literally grinds the codes of the genre, and Ann Hui’s Boat People ; a crushing piece about the life conditions in Vietnam following the end of the war and the story of undesired exile ; that I started exploring the idea of making an educated and educative piece about Hong Kong New Wave cinema. I believe it was in 2013 ; I had just made my first two short films and was therefore very eager to try my hand at just about everything. But it was finally the mindblowing opening to Kirk Wong’s The Club which convinced me that I needed to not just do a piece that dealt with the New Wave ; I needed to approach the entirety of Hong Kong cinema. I was not aware at the time of the gargantuan task I had before me ; which is probably why the project fell into oblivion after a while. Nevertheless, I never completely forgot about the idea ; I think, mainly, the issue was figuring out which shape it was going to take, and the truth is, beyond the title ; Hong Kong Cinema Blues ; which implied a melancholic and nostalgic position on a cinema that has since 1997 fallen to incredible lows ; I had no idea just what on earth I was doing.

The Sword

Boat People

The Club

A link to Kirk Wong’s The Club. The film, while highly influential and important, is profoundly flawed… But that opening scene is the sort that I look at and then think that if I could produce one scene like that in my life I’d be well happy with my film-making career.

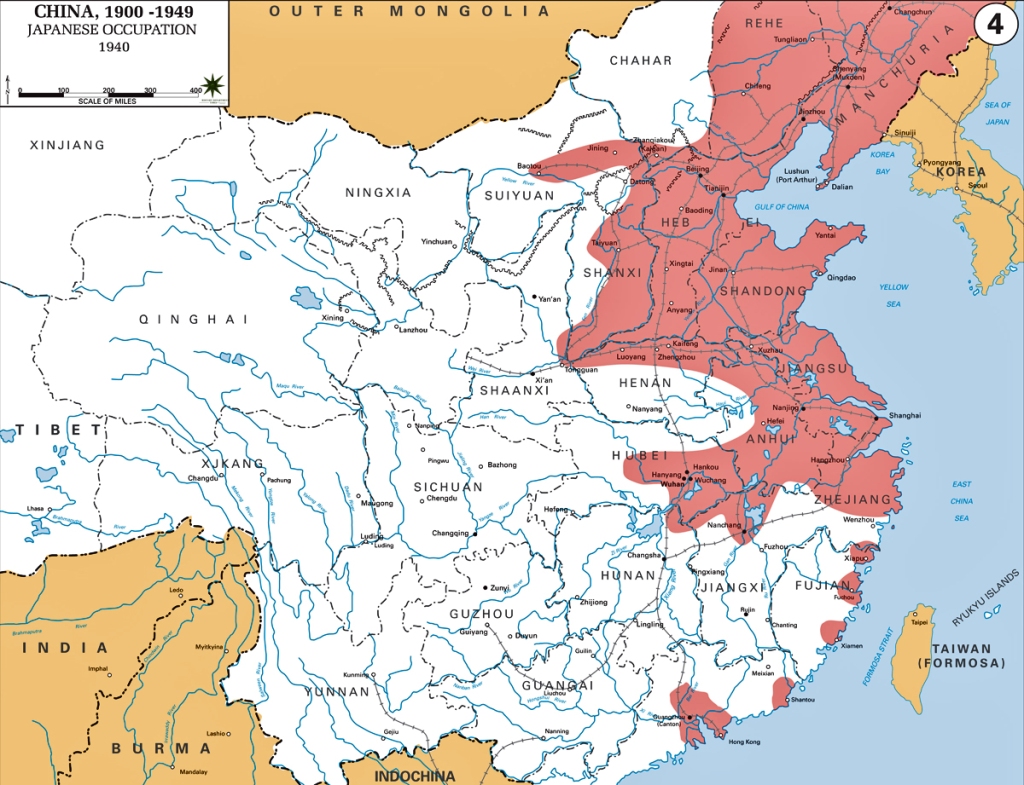

Over the summer, I entertained the idea of going back to this project, but between college and my own professionnal commitments, it felt impossible to achieve, especially considering the work load it would represent. This module, however, with its focus towards editing and post-production represents the perfect opportunity to try my hand at some sort of video essay which would approach at least a part of the history of Hong Kong cinema. And what better than the Hong Kong New Wave? Throughout my years of research, it has been the movement I have focused on most expensively. The films might be rare ; but over the course of the last four years I have managed to find just about all of them, Peter Yung’s elusive The System having popped up out of nowhere this summer. One might as well say I’ve got all my footage sorted, and I don’t even have a narrative yet! But most importantly, the New Wave, as far as Hong Kong cinema is concerned, represents the turning point in its history. It is more than a simple movement : it’s a period of time that is special for the film-makers and film-goers of Hong Kong for the simple reason that it precipitated and ushered in just about everything that followed. A bit of context ; the Hong Kong film industry has existed since the 1910’s, in one form or another, but it was not until the invasion of China by the japanese empire in 1937 that it became a cinematographical entity of its own. At the time, the center of chinese cinema was Shanghai ; there, a film movement that came to be dubbed the ‘second chinese generation’ (as in the second generation of chinese film-makers), was prospering, and prospered well until Mao Zedong’s rise to power in 1949. The japanese invasion of northern China pushed most of the great chinese directors and film technicians south, into Hong Kong. Mao Zedong scared away the rest, both before and after the so-called Cultural Revolution, only keeping a few talented individuals who became the third chinese generation ; Mao’s main source of propaganda. The exodus of film technicians, directors and experts into free, british Hong Kong led to the establishment by two major studios ; Shaw Brothers and the Motion Picture General Investment company ; of one of the most important (in terms of sheer number) film industries in the world.

Vintage posters of old Shanghai films

Throughout the 1950’s and the 1960’s, Hong Kong was the greatest film industry in South-East Asia, and enjoyed a shining and crowning success from Korea to Indonesia through Thailand. The productions of the Shaw Brothers, while cheap, had great production value, were produced cheaply, quickly, efficiently, and in bulk, with a surprising consistency in terms of quality. Such directors as Li Han Hsiang and Chu Yuan, from the sixties, gifted Hong Kong cinema with some of its crowning achievements ; Li Han Hsiang’s Enchanting Shadow, for example, which is a classic whose influence can be felt on works produced by the New Wave and beyond. That golden age, however, started to fade away in the seventies. The MP&GI, unable to keep up with Shaw Brothers’ relentless and ruthless competition, closed down in 1972, leaving Run Run Shaw’s gigantic company to rule alone over Hong Kong, and drown the film market with repetitions of formulae already repeated ad nauseam over the sixties. Soon enough, Hong Kong turned to TV, and unsurprisingly, it is also from television that the New Wave inevitably emerged. Tired of a film industry which had nothing new to offer, and gifted with an energy, a fresh perspective and a taste for the unknown that they all inherited from their studies abroad, they set out to reshape Hong Kong cinema. Yet, their approach was not one of complete rejection of the old, unlike the Nouvelle Vague in France, but rather one of reactualization of the old… Thus, the directors of the New Wave injected traditional genres ; like the chinese chivalry films ; with elements of modern and foreign cinematic mediocrity, or they approached new genres ; like the crime film, which was considered vulgar in Hong Kong at the time ; and infused them with typically chinese classical elements coming from other genres. In that respect, Hark’s The Butterfly Murders is without a doubt the most significant contribution of the New Wave ; the vitality and creativity Hark has brought to the genre through this first feature still influences contemporary Hong Kong filmmakers. Yet, this current of thought and creation finds its most obvious echo in Peter Yung’s Soul of the Wind, a rural drama on the verge of the ethnographical film about an archeologist who must travel to the frontier of China and Kazakhstan to uncover forgotten chinese relics. By seeking the old, Soul of the Wind’s protagonist also finds the new and the unknown, as he embraces kazakh culture to the point that he becomes one of their own and forsakes the city life he once cherished.

The Enchanting Shadow

Soul of the Wind

Yet perhaps the most important element that pertains to most of the films of the Hong Kong New Wave is their sheer madness and fury. As is common with most young filmmakers, the directors and artists were angry about everything. Their complete rejection of traditional Hong Kong cinema, by deciding to work outside of the major studios (meaning Shaw Brothers, as in 1978 there was no competition anyway), was only the beginning. The work of the core auteurs of the Hong Kong New Wave (defined by Pak Tong Cheuk as being Tsui Hark, Ann Hui, Alex Cheung, Allen Fong, Yim Ho and Patrick Tam) stank of rage as early as 1979. The Butterfly Murders is a notable effort, of course, but so is Peter Yung’s The System. Peter Yung, who had spent several years in the Golden Triangle filming documentary work about the drug manufacturing operations existing there before coming to cinema, brought to film a documentary approach that was at the time absolutely new in Hong Kong cinema. Using this approach, he made The System, the story of a cop who turns a drug dealer informant (before befriending him, of course) in order to nab a much bigger fish, but who encounters so much police corruption and bureaucratic incompetence that he just fails. The film’s climax is as harrowing as it is unfulfilling : as the protagonist is mowed down by machetes in a taxi parked in a dodgy alley, he has achieved nothing. And only at that moment do you, as a viewer, realize what the title means : the System is there to help, favorize and encourage evil. The good guys never win… A message which resonated in an industry in which the good guys usually always won. But it is without a doubt Tsui Hark’s last New Wave flick ; Dangerous Encounter of the First Kind ; which is the most enraged. One of the most subversive films ever produced in the former british colony, it depicts a generation who is completely out of touch with reality, out of touch with their culture, out of touch with the environment around them. In 1980, as the negociations to return Hong Kong to China were already under way, Tsui Hark’s notion of entertainment was to depict kids setting off bombs in cinemas, for no other reason than they thought it was fun. Inspired by a newspaper story, the rest of the film is a series of violent happenings that escalate and escalate out of control all the way to a finale that reaches heights in nihilism that Hong Kong cinema has seldom ever achieved. But beyond the nihilism, it is the rage of the man directing and filming that strikes a cord, because that rage, while sublimated by the camera, is aimed at everything. The bombing of the cinema is an obvious metaphor of Tsui Hark’s own ambitions ; to break the local film industry apart ; the people of Hong Kong are portrayed as ignorant and shortsighted, the cops are corrupt or incompetent, and in the end the characters find themselves in a standoff with a group of foreign former military men ; another metaphor for the yoke the rest of the world has made China suffer, and more particularly Hong Kong.

The System

Dangerous Encounter of the 1st Kind

However, fury is only one side of the same coin : youth. Novelty is the second side, and the new wave filmmakers certainly brought a lot of it to Hong Kong. As a generation of filmmakers born between 1946 and 1951, most of the time in families with strong ties in mainland China (or in Vietnam, in Tsui Hark’s case), the directors of the New Wave were inevitably going to bring something new to the table as they stood at the junction of two different chinese cultures : the mainlander culture, and the culture of Hong Kong, which has been profoundly influenced by british occupation. It is no coincidence that all these filmmakers studied abroad and took very similar roads into motion pictures ; however, whereas Pak Tong Cheuk in his amazing book about the New Wave identifies this as an aspect common to all contributors to the New Wave, he doesn’t adress the idea that this common aspect is a symptom of a cultural phenomenon which directly echoed the massive exodus south between 1938 and 1945. Similarly, it is also the idea of going back to a chinese regime which has politically sparked the emergence of a subversive New Wave : while, of course, directors like Tsui Hark and Peter Yung made films that were highly politically engaged and which defied the british establishment, the prospect of returning to the regime which had engineered the Cultural Revolution had Hong Kong in a constant state of terror and anticipation. It also signifies that these young filmmakers’ anger was inherently connected to the political situation in Hong Kong between 1978 and 1984. The New Wave ended in 1984, the same year the final negociations concerning the Handover were finalized, signifying for most of the New Wave filmmakers that there no longer was anything to fight for. During those six years, the New Wave filmmakers fought for change ; change in the industry, social and cultural changes, political change ; but ironically they brought change with them, so much so in fact that they virtually reshaped the industry.

Margaret Thatcher shaking hands with chinese foreign minister Ji Pengfei following the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration, which declared that the United Kingdom would return Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China on the 1st of July, 1997.

Change, first and foremost, came to the Hong Kong film industry through technical innovations. Saying that the Hong Kong film industry, all the way into the eighties, was late behind most of the rest of the world, is a kind euphemism. Chinese cinema only started in the 1910’s, two decades after the USA, France and the United Kingdom started developping their own budding industries. The first generation of chinese filmmakers produced, for the most part, films that were designed to entertain : romances, and wu xia films ; however, chinese cinema failed to detach itself from the traditions of Peking Opera. In the mid-thirties, chinese cinema was still mainly silent ; except for a few efforts by the second chinese generation, which emerged in 1932 and began bringing technical expertise and notions of theory on the table. The second chinese generation made a number of advances, that were all set back or stalled by both the japanese occupation and the third chinese occupation. As a result, when Shaw Brothers and MP&GI set up shop in Hong Kong during the fifties, the chinese film industry was ten to twenty years behind on the rest of the world. Worse, what progress could be made started stalling completely in the sixties when Shaw Brothers took complete control of the market and started flooding it with repeated formulae. A proto-new wave emerged then, between 1966 and 1974. Shaw Brothers produced most of their films in mandarin. However, citizens of Hong Kong speak mainly cantonese. As such, in spite of Shaw Brothers’ control over the market, a parallel cantonese market soon emerged. Cantonese films were, from 1966 to 1978, the main source of qualitative progress in Hong Kong cinema. Patrick Lung was the leader of this alternative movement, and to the best of my knowledge, he was the first director in Hong Kong history to actually tackle socially relevant subjects in a socially relevant manner. The best example of his work is, of course, the film which John Woo would eventually remake into A Better Tomorrow in 1986 : Story of a Discharged Prisoner. The title is self-explanatory ; it’s the story of a man who is released from prison and then does his utmost to find redemption and clear his name in his family’s eyes. He fails utterly, of course, as society, and the triads, refuse to let him. A striking social commentary about a society which refuses to grant moral amnesty to the criminals who fairly serve their time, and which creates its own monsters by actually refusing to take a coherent moral stand, Story of a Discharged Prisoner is also notable for its aesthetics ; shot in black and white and in Academy ratio when most of the industry had converted to scope and color, Patrick Lung’s masterpiece is a daring work of art that has stood the test of time and has made history. Perfectly complimented by Cecille Tong’s The Arch, a romance photographed by Subrata Mitra (Satyajit Ray’s cinematographer) and shot by Les Blank in a striking black and white which is famous in Hong Kong for introducing fades to its industry, both films represent the best this proto-movement achieved before it crumbled under the weight of television, just like the rest of Hong Kong cinema.

Story of a Discharged Prisoner

Stills from the Arch

Television was in cantonese, of course. When the New Wave emerged, it was with a cantonese cinema ; a cinema transformed over the years by the technical and narrative innovations of cantonese cinema. In 1979, the transformation was made obvious by Ann Hui’s The Secret. A surnatural thriller about the murder of a young woman, and the possible involvement of ghosts in the sordid affair, Ann Hui’s first feature is a haunting, strange and disturbing piece of work, not so much of the subject matter or the screenplay ; which are the film’s main weaknesses ; but because of the way Ann Hui approaches story and narration. So far, in Hong Kong cinema, there had been one way : linear narration, ponctuated by flashbacks, images shot in Scope, sound produced entirely in post-production. That was the Shaw Brothers’ way. The Secret was one of the films that said no and found another way. Going forward and backward incessantly in the narrative ; ending her film on a flashback which serves as a reveal to the big mystery ; Ann Hui blurs the limits of rationality and reality, creating in the viewer’s mind the essential doubt that make the fantasy elements of the film function as part of the story. Jump cutting, lighting directly evocative of the italian gialli… Minute upon minute, The Secret brought something new to the visual grammar of Hong Kong cinema, in a way that even Tsui Hark could not match.

The Secret

The New Wave encountered commercial successes, against all expectations. While those successes were moderate, they eventually brought light upon the directors who animated it. This eventually led Shaw Brothers to seek out some of those directors ; who, for the most part, had worked in the television subsidy of Shaw Brothers, TVB. Those who did not join Shaw Brothers joined Cinema City, a production society which emerged in the early eighties and started eliminating the possibility of a New Wave by producing cheap (often mediocre) films and investing most of their money into communication and promotion. This led to a gradual absorption of the New Wave into the Hong Kong mainstream, and while it was mostly completed by 1984, with Tsui Hark’s founding of the Film Workshop, it continued well into the 1990’s thanks to artists like Allen Fong and Yim Ho, who rejected the insertion and continued producing independent movies to the best of their ability ; often with great artistic success. That absorption into the mainstream, however, started as early as 1981, with Clifford Choi joining Cinema City in 81 then Shaw Brothers in 82. While many local critics qualify the notion of absorption into the mainstream as negative, it is once the directors of the New Wave were truly assimilated in a system which enabled them to work on bigger budgets and promote their work more effectively that they produced their best works and spread their technical and narrative innovations. And so it was in 1984 that Tsui Hark propelled the New Wave into the bigger world of Hong Kong motion pictures with his heart-rending Shanghai Blues, a masterpiece of vaudevillian comedy which references both Gone with the Wind and classics of the second chinese generation like Yuan Mu-Zhi’s Street Angel through a sweet, innocent yet profoundly mature love triangle craftingly designed to reactualize the importance of such classics within the logic of Hong Kong cinema. Beyond the ambition of Shanghai Blues ; to bring subversion into a genre as popular as romance and comedy ; the film marks both the end of an era and the beginning of another. Tsui Hark, after a few years at Cinema City and a stint at Golden Harvest which almost led him to abandon cinema, refused to work for the big studios and decided to make his own nest : Film Workshop. In the years that followed, Tsui Hark used his studio and his subsequent successes to produce the works of a number of New Wave auteurs : Kirk Wong, Ann Hui, Yim Ho, Johnnie To all contributed to Tsui Hark’s gargantuan project of reinjecting vitality, subversion and power in an industry he considered to be moribond.

Shanghai Blues

Street Angel

However, long before the Hong Kong New Wave ended, its impact and influence was already established. The absorption of New Wave auteurs into great studios like Shaw Brothers is only revelating of a symptom which, at the time, gripped the industry : because it was moribond, and because the studios now failed to exploit and cash in on the old ideas they depended on, they brought in new blood. Clifford Choi was the first. Peter Yung followed in 1981 only to return to auteur films in 1982 and finally to documentary and TV in 1987. But it was not until 1983 that one of the core auteurs of the New Wave finally joined Shaw Brothers, in 1983, to direct one of the first science-fiction efforts ever produced in the old colony ; a film designed to be the Hong Kong response to Star Wars which soon became the most expensive film ever produced in Hong Kong at the time… The impossible to describe Twinkle Twinkle Little Star. The gamble failed to pay off, and contributed greatly to Run Run Shaw’s decision in 1985 of abandoning the film aspect of his company, but his 1983 decision to allocate the year’s largest film budget to a New Wave auteur was itself motivated by 1. Golden Harvest and Cinema City’s ruthless competition ; 2. the freshness and the creativity that the New Wave were bringing to the table. Why Alex Cheung? Because as a filmmaker, his contributions to the movement were more than important ; they were instrumental in establishing the crime and police film as a traditional genre in Hong Kong. Between The System and Ronny Yu’s The Servants, 1979 was rich in crime films, but it’s Alex Cheung’s Cops and Robbers which stands as the most seminal effort produced in this genre this year. A socially conscious look at the relations between criminals and policemen and the common people’s rejection of the police as being a symbol of authority designed to oppress them, Cops and Robbers created a short-lived sensation in 1979 thanks to its bleak representation of urban life, its impeccable dramatic construction and its insane finale, which, on top of being one of the most visceral things produced in Hong Kong in the seventies, pays itself the luxury of being six years ahead of William Friedkin’s To Live and Die in L.A. Unsatisfied with this success, Cheung reiterated two years later with the gripping Man on the Brink ; the matrix for all undercover cop movies produced in Hong Kong subsequentially, and a nihilistic tale of social corruption and apathy ; while Kirk Wong brought to the genre a purely chinese perspective with The Club, historically the first contemporary gangster film to heavily feature highly-choregraphed and thought-out kung-fu scenes ; thus anchoring the genre into a truly chinese tradition that would later be further explored by Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung.

Cops and Robbers

Man on the Brink

The Servants

And that’s it for this week! Logging out now with a piece of sheer Hong Kong New Wave madness coming straight from Kirk Wong’s weird cyberpunk flick Health Warning.

Next week, I’ll discuss the critical argument I wish to develop in my short documentary, and possibly what form this argument will take.

THE FILMS OF THE NEW WAVE

1978

1979

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

Hong Kong New Wave Cinema (1978-2000) (2008) Pak Tong Cheuk

Reference list :

- A Better Tomorrow, John Woo, 1986 (Hong Kong)

- The Killer, John Woo, 1989 (Hong Kong)

- The Butterfly Murders, Tsui Hark, 1979 (Hong Kong)

- Hong Kong New Wave Cinema : 1978 – 2000, 2008 (Hong Kong)

- The Extras, Yim Ho, 1978 (Hong Kong)

- Homecoming, Yim Ho, 1984 (Hong Kong)

- The Sword, Patrick Tam, 1980 (Hong Kong)

- Boat People, Ann Hui, 1982 (Hong Kong)

- The Club, Kirk Wong, 1981 (Hong Kong)

- The System, Peter Yung, 1979 (Hong Kong)

- The Enchanting Shadow, Li Han Hsiang, 1960 (Hong Kong)

- Soul of the Wind, Peter Yung, 1982 (Hong Kong)

- Dangerous Encounter of the First Kind, Tsui Hark, 1980 (Hong Kong)

- Story of a Discharged Prisoner, Patrick Lung, 1967 (Hong Kong)

- The Arch, Cecille Tong, 1969 (Hong Kong)

- The Secret, Ann Hui, 1979 (Hong Kong)

- Shanghai Blues, Tsui Hark, 1984 (Hong Kong)

- Gone With the Wind, Victor Fleming, 1939 (USA)

- Street Angel, Yuan Mu Zhi, 1937 (China)

- Star Wars, George Lucas, 1977 (USA)

- Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, Alex Cheung, 1983 (Hong Kong)

- The Servants, Ronny Yu, 1979 (Hong Kong)

- Cops and Robbers, Alex Cheung, 1979 (Hong Kong)

- To Live and Die in L.A, Alex Cheung, 1985 (USA)

- Man on the Brink, Alex Cheung, 1981 (Hong Kong)

- Health Warning, Kirk Wong, 1983 (Hong Kong)